Medical Care: A Historical Perspective

Written by Louise Ryland-Epton

I think we all feel a great debt at the moment to the NHS. Being a historian, however, I cannot help but also reflect on its earlier local antecedents.

The earliest evidence for any kind of local health care system in Bremhill comes from the 1760s. One of the earliest patients was a widow, Rebecca Harden. Rebecca was the grand age of 93 when she fell ill in July 1763. Unfortunately, we do not know precisely what was wrong, but she had a wound or sore which required dressing. For five days, she received a daily home visit from a parish appointed medical practitioner who also dispensed her medication. Neither Rebecca nor her family had to pay anything for her care which amounted to over seventeen shillings. The cost was instead met by the parish poor rates, a village tax which was charged on the occupiers of local property.

At the time, it was not a requirement of the law for parishes to provide medical care; instead, it was a decision taken by local people.

Medical Care: A Historical Perspective

In fact, Bremhill parish did not provide one medical practitioner but several including Mr Wheeler, Mr Goddard, Mr Scott, and Mr Wise, who was the physician that treated Rebecca. It is difficult to know why there was more than one; possibly the physicians had different specialities, maybe several were needed to cover the large geographical area or perhaps the work of providing care to the poor was shared amongst local medical men and one woman, Mrs Roman. Early medical bills indicate the services they offered consisted of visits and prescriptions for ointments, powders, syrups, tinctures, pills or draughts often for 'purging.' Treatments also included the application of blisters, bleedings and vomiting. The efficacy of many of these remedies is doubtful. When Edith Smith was treated for dropsy (oedema) in the same month as Rebecca, she also received several home visits. She was made to vomit, prescribed powders and given honey-sweetened diuretic designed to ease her symptoms. The following month she was given ‘strengthening pills’ possibly to build her up again after her recovery. While the underlying cause of her oedema may not have been serious and the treatment possibly completely ineffective, evidence suggests that local medical practitioners were also trying to treat and cure the most serious diseases. And sometimes we can be reasonably confident they met with some measure of success.

Probably the most feared disease of the age was smallpox. It was extremely contagious, and the risk of death once contracted, was 1 in 3. Those who survived could be made blind or at the very least extensively scarred. In the early 1770s, smallpox appeared in Bremhill.

Smallpox

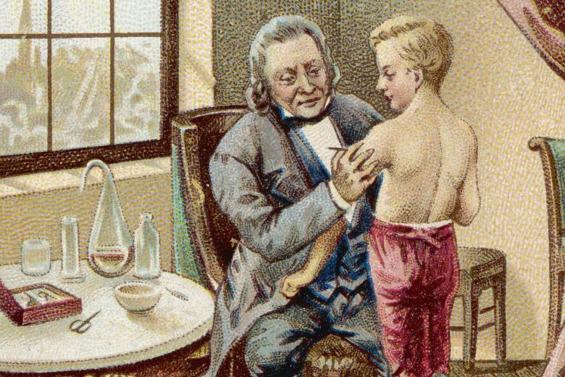

Robert Wickes was very poor and had received parish welfare for a few years, probably related to a physical disability affecting his ability to work. (He is described locally as a ‘crippel.’) Robert’s unnamed daughter began to exhibit the symptoms of the disease in early April 1773. She was referred to the ‘eminent’ local physician, Christopher Allsup, doctor to the Lansdowne family at Bowood. Allsup’s treatments included juleps for fever, linctus for a cough, ‘anodyne draughts’ for pain, ointment for the sores and ‘alterative bolus’ probably designed to cure the affliction. He visited the girl on several occasions, and she was given attendant nurses, who presumably looked after the patient in shifts. The patient and her carers appear to have been quarantined from the rest of the Wickes family. One cannot but be impressed with the bravery of Allsup and these unnamed individuals, who in simply providing care, knowingly put themselves at immense risk, centuries before adequate personal protective equipment. Possibly most impressive, there is evidence Allsup also took the unusual step of inoculating the nursing staff, which included a ‘man nurse’, against the disease. It was decades before Edward Jenner discovered the smallpox vaccine which eradicated it during the twentieth century. At the time, Allsup would have had to infect these attendants with a mild version of the disease, a process beset with risk, but which provided life-long immunity. It is very difficult to know the outcomes, but Robert’s daughter did not die, nor did any other member of her immediate family or Allsup himself. Neither was there a discernible spike in local deaths. It is credible, therefore, that on this occasion, medical intervention saved lives.

Unfortunately, as they are anonymous, I cannot be sure what became of the nurses. I can only hope like some of the staff on the frontline of the present pandemic they did not succumb to the disease they were trying to treat.

Notes: Several itemised medical bills have survived which provide wonderful insight into local medical practitioners, their treatments and those individuals they cared for. See: - W.S.A., 1195/28. Some of these names I have cross-referenced with parish registers and overseers accounts.

Medical Care: A Historical Perspective