Wilts and Berks Canal

Written and illustrated by John Harris

Wilts and Berks Canal

Birth of the canal through the parish

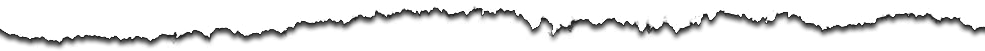

The demand for coal from the Radstock and Paulton mines in Somerset spawned the Somerset Coal Canal which eventually joined the Kennet and Avon Canal helping to take trade to Bath and Bristol and eastwards to the Thames linking the South West to the Midlands. At the end of the 18th century raw materials for the Industrial Revolution were in huge demand, this included stone for roads in addition to coal and these materials could easily be carried by water transport where canals existed.

North Wiltshire and West Berkshire were little served by navigable waterways so an incentive to expand the canal network was a clear trade opportunity.

In January 1793 a meeting was held at Wootton Bassett Town Hall to promote a new canal from Abingdon linking with Bristol. Many further meetings ensued with shareholders of the venture agreeing the appointment of Robert Whitworth, Chief engineer and his son William to survey the landscape and draw plans accordingly. A year later after many variables a final plan was put forward to join the Thames at Abingdon and link to the Kennet & Avon Canal at Semington. As soon as the plans were published many objections were raised. Locally, a tenant farmer claimed that a stream across Christian Malford Common was essential to the prosperity of his holding and should not be tampered with. Many other similar rights were protected and the Bill for commencement was granted by The House of Commons and The House of Lords in April 1795. This included navigable cuts From Bremhill to Calne and Pewsham to Chippenham. The company of proprietors included the Marquis of Lansdowne, Earls of Peterborough, Clarendon, Radnor and Carnarvon.

Construction began later that year of the Calne branch, part of which ran across Bremhill parish. The largest engineering work on the whole canal line was in the main canal section near Stanley and required a brick and stone aquaduct across the River Marden. Whitworth designed the structure with two twelve foot arches which was built on dry land on one side of the river, the waterway was then diverted through one arch whilst the other was built.

Impression of how the Stanley Aquaduct might have looked in its early days

Another example of his clever thinking was his rationale to create brick works at strategic points along the canal route. One such brick yard was at Stanley and another at Foxham utilising the Kimmeridge clay that is prevalent in the Marden Vale. He had also worked out that if he extended the length, depth and width of the standard brick size then the job would cost less and get done more quickly! As the canal progressed one brick kiln was closed and another built nearer to the construction site and so on. The actual work of building the canal was done by ‘navvies’, a term which was an abridgement of the less poetical word ‘navigator’. A historian of the time described them as ‘displaying an unbending vigour and an independent bearing, mostly dwelling apart from the villages near where they worked with all the properties of an untaught, undisciplined nature’. Not everyone agreed with this picture, Brunel, for example thought that navvies were manageable if well treated.

1810 - Open for navigation

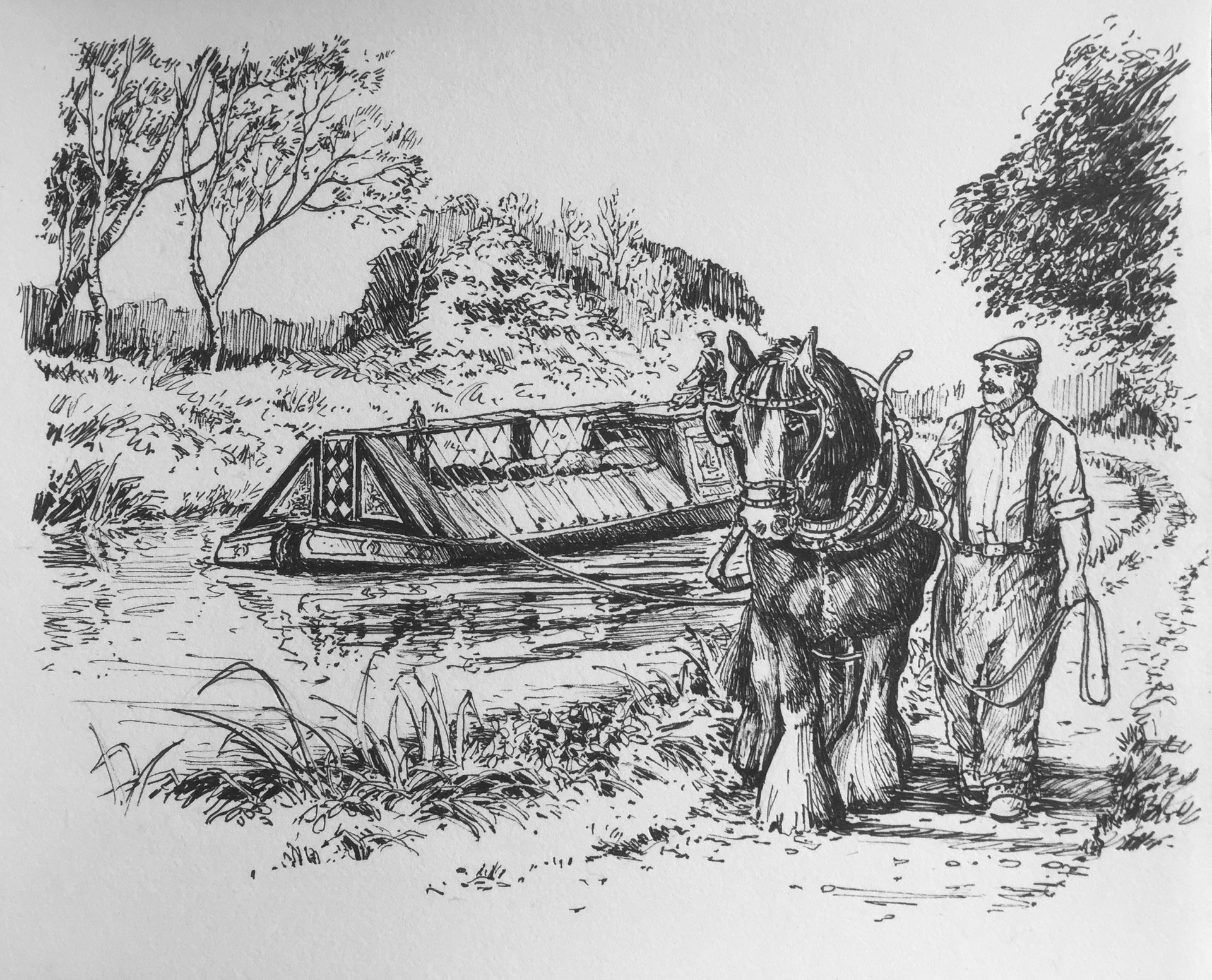

Opening of the completed Wilts & Berks canal was in September 1810 when the 52 miles of the canal finally reached the River Thames at Abingdon where there was much revelry, flag waving and music until the early hours. The canal traded satisfactorily for a few years with Chippenham & Stanley Wharf and Calne and Foxham Wharf trading with an average of 4,000 tons of coal per annum during the heydays of the 1840’s. Whilst the Great Western Railway became a major threat to its eventual decline the building process of the railway provided a huge boost in income as a massive tonnage of stone, metal and equipment was carried by the canal infrastructure. An idea of how the canal faired in trading terms can be gauged by sampling the number of tolls collected each year during its lifetime. In 1810 it was 3,164 tolls, 1822-7,724 tolls, 1830 -9,755 tolls. In 1840- it was at its highest at 9,000 tolls and then there was gradual decline to around 600 in 1893. In 1901 Wiltshire County Council agreed that it was in such a state of disrepair that it was of no use for waterway traffic. The Wilts & Berks syndicate applied for an Act of Abandonment which was finally made in 1914 although the canal was practically rendered impassable at the southern end when the Stanley aquaduct developed a large hole in the canal bed in 1901 and all the water drained into the River Marden between the lock above and the lock below. The ‘death knell’ came when one of the arches collapsed in 1906.

In all there were forty two locks on the main line and three on the Calne branch with three short tunnels overall. The canal was capable of taking boats up to 72ft. in length but a vast majority were around 45ft weighing 20 tonnes unladen because of the narrow width and depth of the canal. Water was always a problem and a reservoir was constructed at Coate near Swindon which was the summit of the canal system.

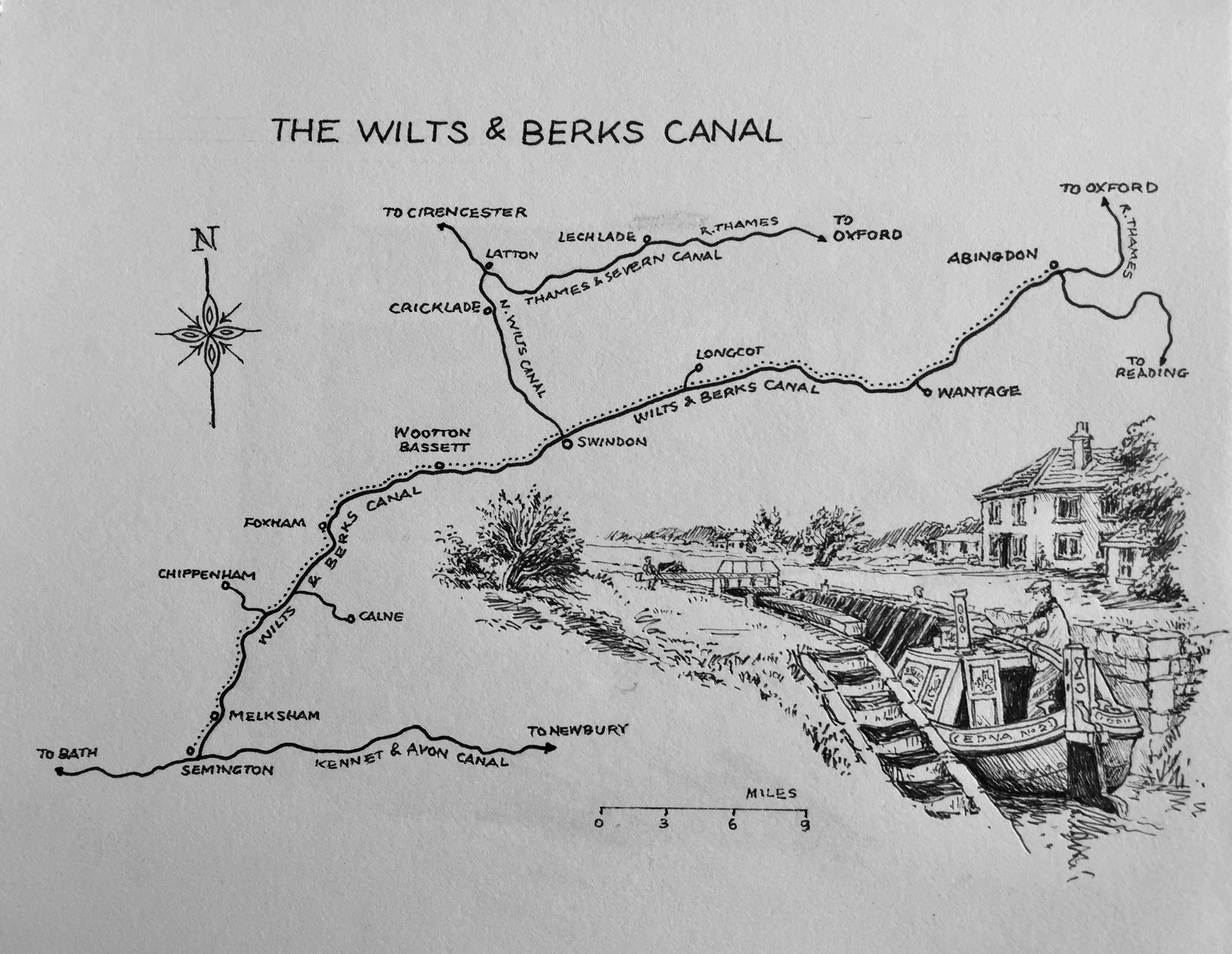

Horse-drawn laden narrowboat near Bremhill Grove in 1815

The southern approach to the canal enters Bremhill parish from the direction of Forest Gate where the A4 crosses the canal. It then follows the line to Studley under a minor road bridge passing under the disused Calne Branch railway, now a Sustrans cycleway and footpath, to the site of what was the largest engineering work on the main line, the aquaduct over the River Marden with two arches, now non -existent. Two deep locks, Stanley top and bottom lifted the canal passing the entrance to the Calne branch and onto Stanley Bridge and Stanley Wharf site of the wharfinger’s (manager’s) house, now a private domain. Beyond that Wick Arched Bridge features along with a draw- bridge at Bremhill Grove. The next road intersection is at the bottom of Charlcutt hill by a small cut which was for overnight mooring and loading. During the Second World War many of the locks and other canal structures were used for army exercises and damaged by explosives including the Charlcutt canal bridge. Between there and Foxham the canal ran in open fields under two draw-bridges and over a substantial culvert spanning the Cade Burna stream. The canal passed east of Cadenham Manor built in the second half of the seventeenth century under a bridge on the Foxham to Hilmarton road to ‘climb’ the hill via Foxham bottom and top locks. The latter is now restored and the canal is in water for a mile. As it leaves the parish there are two restored lift bridges and evidence of another. As mentioned before the Calne cut was entered at Stanley just north of the aquaduct and continued through open fields until it ran beside Hazeland Mill, recorded in use as a cloth mill until c1835 and as a grist mill until c1965. The canal then left the parish running beside the River Marden before entering a tunnel under what is now the A4 and onto the centre of Calne.

Impression of a laden narrowboat passing a lift bridge near Foxham circa 1895

Family life on a trading narrowboat

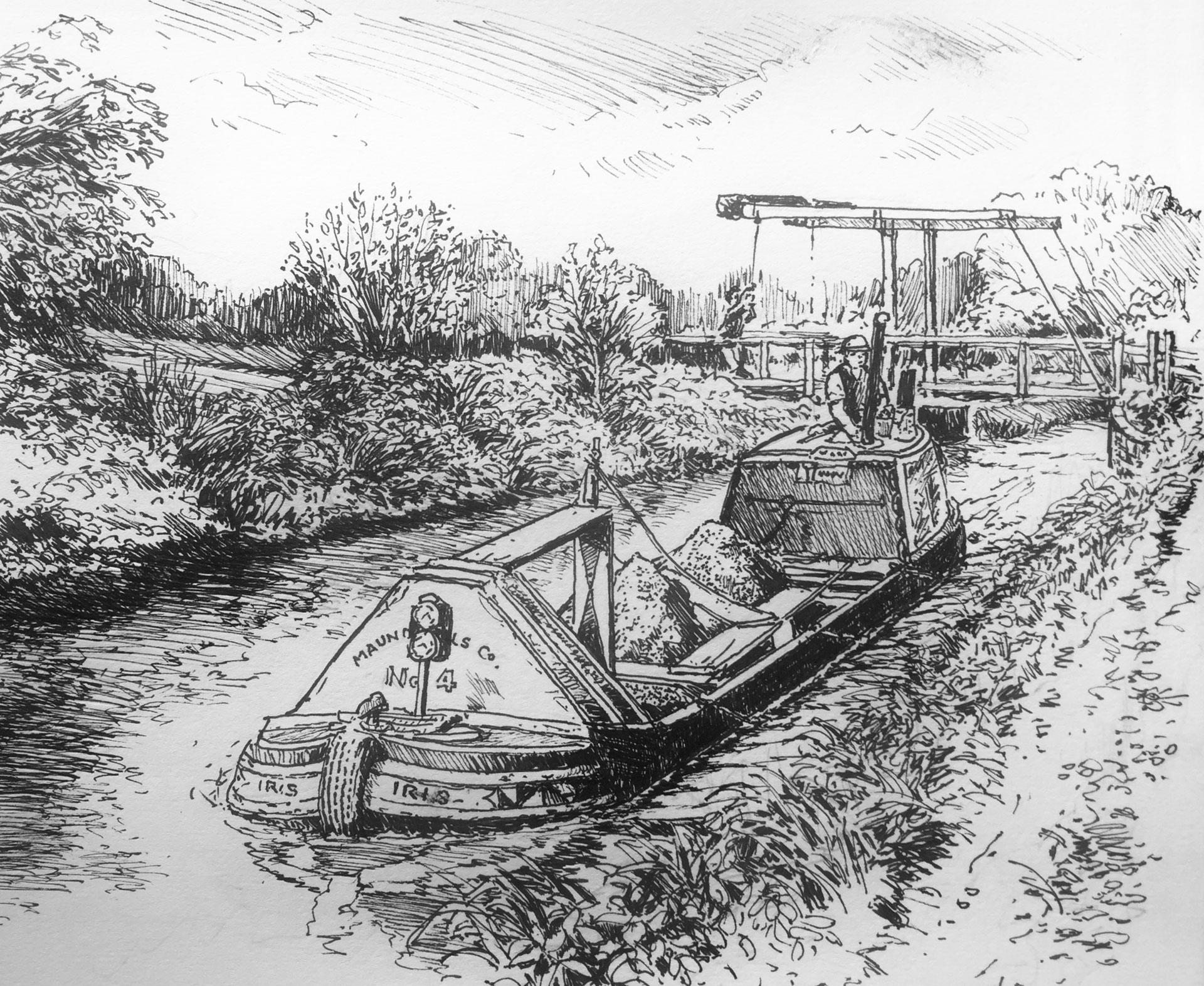

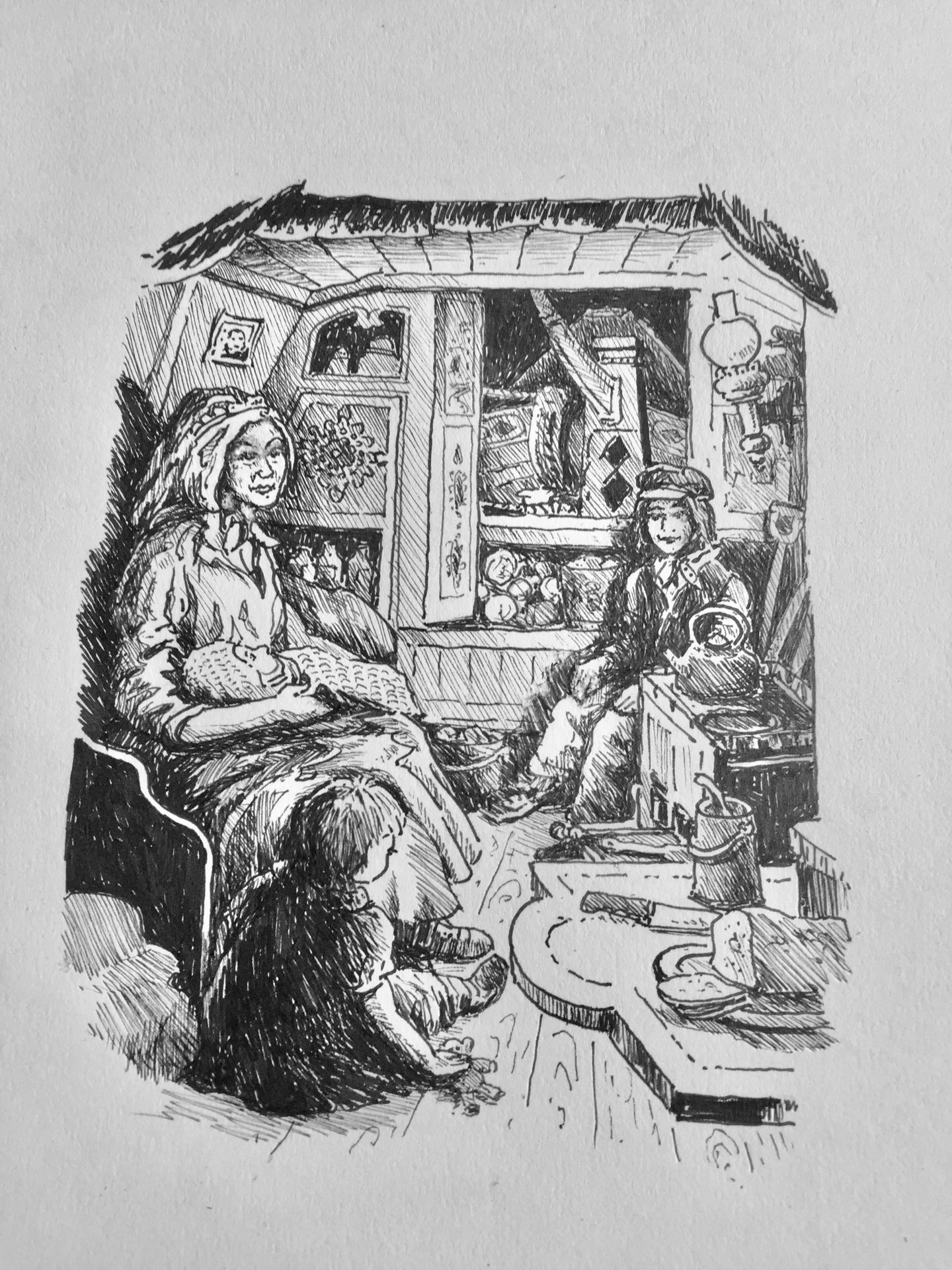

Boat people lived in a closed community. Most boat people were born and brought up on the canals and they tended to marry boat people, possibly nobody else fancied the life and hard work. Some did take jobs on dry land, especially when trading was collapsing due to the development of the railways. In the early years of the ‘Ippey Cut’, (so named as it thought to be derived from Chippenham) boatmen brought up their families in the tiny cabins of their horse-drawn narrowboats, cut off by their nomadic lifestyle from the schools, hospitals and even religion. By ingenuity and evolution the narrow boat living cabin came to be bedroom, bathroom and kitchen for the family in a space little bigger than a ten foot by six foot container. Bunk seats were built in as storage boxes, the bed folded up into a cupboard, another cupboard folded down to become a table , an open drawer became a child’s bed for the night and a coal fired stove or cooking range in the corner kept it warm. Every available bit of space was utilized just to get everything in. Add a family, and curtains, saucepans, clothes and ornaments and the result is a truly extraordinary living space by any criteria. A space which to this day is upheld on traditional narrow boats, even those with modern engines. The inside of the cabin was often painted cream and ‘combed’ with brown paint to create grained patterns emulating the grain of wood, this was called scumbling. Cupboard doors and drawer fronts were made with panels that had colourful pictures painted on them. The decoration was influenced by the Victorian style of the time, which meant lots of frills and fancy items. Even in the beautiful countryside newly cut canals would have looked untidy and bland until nature softened them so it is not altogether surprising that the cabins became a riot of decoration and applied art. The canal boat people were an insular part of society which gave rise to an emergence of a distinctive and decorative art form providing an identity and which gave the few possessions that they had an increased individual status.

The Boatman’s Cabin was barely 10’ long and housed an entire family

Roses and Castles

The tradition of painting panels with a landscape the subject matter of which is a castle with turret, a stream flowing improbably through an arch in the castle to a lake with mountains in the background and a sunset probably came from Romany gypsies employed as navvies in the making of the canals. Their traditional horse-drawn painted caravans would have had strong influence on a waterborne community seeking a visual identity from the pundits that were already calling them ‘water gypsies’. It could also be that some Romany gypsies whilst ‘navvying ‘saw that swapping their own existence for a family life working on the water was attractive given that their ability to work with horses was proven , their love of brasses and that they already had experience of living in a cabin space roughly the same size as a trading narrowboat.

Floral decoration may well have had its origins in folk art emanating from the painted furniture introduced by the Adams brothers in the late 1700’s further exacerbated by Sheraton with furniture decorated by roses and floral wreaths which also appeared on long case clocks. Boat painters looking for inspiration would have easily have adapted the subject matter into a brush style of ‘one stoke’ petals and leaves which became the boat painters technique.

As ‘canal mania’ developed during the industrial revolution exterior boat painting became more of a branding exercise coupled with personal decoration. The carrying companies increased in number and there was a need to identify boats at a distance so lock-keepers could prepare locks and wharfingers could make-ready for mooring up and unloading. In the same way that logistics companies brand a multiple fleet so narrow boat companies had their own recognisable livery.

The various canals also had their own symbolic paint application on both sides of the fore end of the boat which identified the company and where they had come from. In the south the name of the boat was usually included on the top bends as it was a requirement of the River Thames regulations. At the stern end the simple design painted on the closed cabin doors became a trademark of the boat company and is said to have its derivation in the livery of horse drawn carts and waggons for the same reasons of identity. The cabin doors were made to a standard pattern and as they spent most of their time open the top panel was painted with a castle scene and the bottom panel with roses. The sides of the stern cabin were painted with the ownership, registration numbers and individual fleet numbers which were required for toll recording and bye laws.

A typical regulation (4) was worded as follows-

Every Owner, Master or Person having the Care or Command of any Boat, Barge or other Vessel passing upon said Canal shall cause his Name and Place of Abode, and the Number of his or her Boat, Barge or other Vessel, to be painted in large White Capital Letters and Figures on a Black Ground, three inches high at the least, and of a proportionable Breadth on the Outside of the Head or Stern of every such Boat… higher than the place to which the same shall sink into the Water when Full Laden.

This became a reason for the carrying company to emblazon its name across the side as an unmissable advert, a practice which has found its way onto vehicle transport to this day.

Canal-life, clothing and food

Generally boat women in the 1800s wore an ankle-length skirt and a blouse, which needed to be practical. The skirt had to be full enough to frequently step on and off the boat and the blouse loose enough round the sleeves to allow full movement when they were steering ‘on the tiller’ An apron, usually white, protected the skirt and a shawl and traditional woman boaters bonnet kept the women warm and protected from the weather. Everyday clothing for the menfolk were corduroy or moleskin trousers, canvas shirts and waistcoats. Colourful neckerchiefs were often worn around the neck but the accent was on hard wearing cloth and above all heavy industrial boots.

Many boatwomen made their own and their family’s clothes by necessity, some using a hand operated sewing machine. Best women’s clothes were often decorated with embroidery and crochet work. Frequently though, a large family with limited income were given second-hand clothing from boaters’ missions. These large families raised in the confines of the boatmen’s cabin became the subject of the Canal Boat Act 1877 which among other things, aimed to limit the number of people that were allowed to live on a boat. This depended on the type of boat and how many cabins it had. Children above 12 (girls) and 14 (boys) years old were counted in the same way as adults and there were strict rules as to where they could sleep. Inspectors were sent along the towpath to ensure the rules were being followed but families often saw the inspector coming and sent their children on ahead!

Food and drink often had to be taken while the boat was underway which meant that cold food or sandwiches were the lunchtime meal with hot food prepared after mooring up in the evening. Food was cooked on a coal stove which also served as the heating which was often turned off in summertime so cold meals were common. Shops were often far apart on the Wiltshire and Berks so boat people supplemented their diet by fishing for eels and pike and sometimes poaching became a necessity. They also gleaned from the fields, hedgerows and occasionally from canal side gardens!

Epitaph

Despite the pressures of a hard existence and unrelenting work on the boats including bulk, dirt producing cargoes there was generally an expression of tidiness and living in a bright colourful environment albeit squeezed into a pint pot. While you undoubtedly had to keep your wits about you steering the boat around weed and obstacles or walking alongside the horse to keep it going on the towpath, there must have been some peaceful moments in the stretches running through the engaging Bremhill parish countryside. One can imagine a friendly wave to Mr Pavey, the miller at Hazeland grist mill or a returned stare from one of the cows at the cattle drink by Elm Farm. From the middle to the end of the 18th that peace would have been shattered by the sound of the great G.W.R. iron horse, steam billowing and the burgeoning noise of metal turning on metal, announced by the rapid exit of the canal -side heron and the springing teal from their hiding place in the rushes. The boatman and the gongoozaler alike would have gazed in awe as the train whooshed past not knowing that it was the agent of a decline and eventual closure of a way of life on the canal.

Abandoned in 1914, the rural nature of stretches of the navigation of the canal, Bremhill parish being foremost in this category, could well be the salvation of its future as it has been in restoration since 1977 by the Wilts & Berks Canal Trust. With much of it now filled in or built over it is a formidable task and is arguably one of the biggest tasks of its type in the country.

Bibliography and reference The Wilts & Berks Canal - L.J. Dalby Wilts & Berks Canal Revisited - Doug Small Narrow Boat painting - A.J. Lewery canaljunction.com auntiemabel.org Wilts & Berks Canal Trust